- Home

- Gordon Korman

Linked Page 4

Linked Read online

Page 4

Big news from the dinosaur dig: They found a Camptosaurus skull fragment about the size of a paint chip. The scientists are pretty amped up about it, but not half as amped up as my father.

“This is exactly what we needed!” he crows. “A huge chunk of good news to take all that swastika nonsense off the front pages!”

“I wouldn’t use the word nonsense,” Mom calls over the electric motor of the treadmill in the den. She’s been on a fitness kick lately—I think it helps her keep her mind off the problems at the school.

“You’ll see!” Dad exclaims. “Now that the dig has produced something exciting, the publicity is going to start pouring out of here. It’s happening just the way I pictured it.” He sits down at the computer and opens a Google search.

I’m relieved. Dad’s already warned me about how sorry I’ll be if Wexford-Smythe University pulls out of here because they don’t like having fertilizer dumped in their mail slot. In his eyes, the peat moss prank put my future in jeopardy. But there’s nothing like a brand-spanking-new hundred-million-year-old paint chip to keep a guy’s future on track.

Dad’s brow furrows and the pounding of his fingers on the keyboard becomes downright violent. “What’s the matter with these people? Where’s my skull fragment?”

I hear Mom speeding up on the treadmill in the den.

I peer over Dad’s shoulder at the screen. The search for keywords Camptosaurus skull brings up websites advertising Realistic dinosaur interaction and Model Camptosaurus skeleton, ages 7 and up (swallowing hazard). When he adds Wexford-Smythe University, we get pictures of a tree-lined campus and the course syllabus for their infrared astronomy program.

“Try Chokecherry,” I suggest.

I wish I hadn’t. When he types the name of our town into the search field, a single word jumps out at us, appearing seventeen times on the page: Swastika.

Third Swastika Appears at Chokecherry Middle School … Swastika Graffiti Rattles Mountain Community … Sheriff Baffled by Swastika Incidents … Swastikas Dredge Up County’s Racist Past.

It goes on and on.

“No wonder everybody hates the media,” Dad complains bitterly. “Leave it to them to focus on the negative and ignore a major scientific find!”

I can’t see Mom on the treadmill, but she must be running pretty fast. Her footsteps are rat-tat-tatting like a machine gun.

I point to one of the results in the middle of the screen. “Wow, ReelTok. He’s one of the top vloggers on the web!”

Dad’s brow furrows. “Vloggers?”

“Video-bloggers,” I translate. “Everybody follows ReelTok.”

He glares at me as if I’ve done something evil. “Really? You’ve heard of this guy?” He clicks on the link.

A YouTube clip opens up, and there’s the famous face of Adam Tok, the internet personality who calls himself ReelTok. As always, he’s so close to the camera that the frame shows him only from eyebrows to mid-chin. It makes him seem even more intense than he already is, with his burning eyes, rapid-fire clipped speech, and slight lisp.

“I read your comments, TokNation. Get out of the city, you tell me. Get away from the crime and the garbage and the fights to the death over a lousy parking space. Find a small town with fresh air and friendly people, where the night jasmine wafts like perfume in through your windows. Wonderful idea!” Suddenly, his unibrow arches into a V and his cheeks flame red. “How about Chokecherry, Colorado, where they paint swastikas at the middle school?”

Dad hits the escape key, and ReelTok disappears. “What’s with this clown, Link? It says he’s from New York City. What’s it his business what goes on around here?”

“That’s ReelTok’s trademark,” I try to explain. “He starts off speaking reasonably about something and pretty soon he blows his stack and starts yelling. It’s hilarious.”

“But why is he yelling about Chokecherry?” Dad demands.

“It’s nothing personal. He can freak out over anything. You should have seen the episode he did when his Wi-Fi went out. He blamed it on God.”

My father is furious. “If you find this hilarious, then you deserve the kind of future you’re going to get. This man has never been to Chokecherry. He knows nothing about our community. But it’s just fine for him to slander us to millions of people on the internet.”

“He’s joking,” I insist. “Today it’s Chokecherry. Tomorrow it’ll be something else. The weather. Gas prices. Chocolate milk that isn’t chocolaty enough.”

Dad is adamant. “The chamber of commerce should sue. I’m going to put it to a vote. No one has the right to lie about our town.”

“Technically, he didn’t lie,” I point out. “The swastikas at our school are one hundred percent real.”

Dad brings down the cover of the laptop so hard it’s a miracle there aren’t computer keys bouncing off the ceiling. “I’m going for a walk!” he rasps, and is out of the house in a flash, slamming the door behind him.

In the silence, I notice that the treadmill isn’t going anymore.

“Short workout today,” I observe to Mom.

But when I poke my head into the den, I see her slumped on the loveseat looking like she’s lost her last friend.

“What’s the matter?” A terrible thought occurs to me. “Did Dad invest all our money in Dino-land?”

She’s surprised. “No, nothing like that. We’re fine. We just wouldn’t be filthy rich, which is okay with me.”

“So what’s bugging you? I know Dad flips out when there’s swastika news, but he always calms down in the end.”

“Swastika news,” she repeats wanly. “I never thought ‘swastika news’ was something we’d have to worry about in our lives.”

“We don’t,” I insist. “I get that swastikas are dangerous when Nazis and white supremacists use them. But this is probably just some rotten kid.”

“Maybe,” Mom says dubiously. “But I don’t like these stories about the seventies and burning crosses. If that’s coming back—”

“It isn’t,” I promise. “And even if it was—I mean, it’s not right and all that. But it wouldn’t be a threat to our family.”

To my amazement, two big tears squeeze out of her eyes and roll down her cheeks. I’m blown away. I’ve never seen her cry before.

“Are you okay?” I ask.

She answers with another question. “Have you ever noticed about my relatives … how all my cousins are on Grandpa’s side and not Grandma’s?”

I don’t know what I expected her to say, but that wasn’t it. “I never thought about it,” I admit. “But it makes sense. Grandma grew up in an orphanage, right?”

She nods. “Right. In France. Did you ever consider what that might mean?”

I’m mystified. “That we’re part French?”

That brings on a watery smile. “I suppose we are. But that’s not the point. Grandma never knew her parents, but she wasn’t orphaned at birth. Her parents gave their baby to the nuns to save her life.”

“What?” This is a part of the story I haven’t heard before. “Why?”

“It was 1941,” Mom explains. “France was under Nazi occupation. My grandparents gave up their baby girl because they were about to be arrested and sent to a concentration camp.”

“A concentration camp?” I echo in shock. “What did they do wrong?”

“Don’t you get it?” she demands, fighting back more tears. “My family is Jewish. The nuns raised Grandma as a Catholic child, but she’s Jewish too.”

This isn’t making any sense to me. “No, she isn’t! We were there last Christmas! They had a tree and everything!”

“She never knew,” Mom tells me. “Not until three years ago, when the convent released its records. She was the only survivor in my family. Her parents and all her relatives died in the Holocaust, murdered by the Nazis. By the time she found out, she had lived almost eighty years as a Christian woman. She’d married and raised her family in the faith. That’s how I was brought up.

But I know what my background is—and now you know yours.”

I’m stunned. “We’re Jewish?”

“Well, your dad’s not. And I’m only half, which I guess makes you a quarter.” She puts a reassuring hand on my shoulder. “Nothing’s different, Link. We’re still the same people. It’ll still be Christmas and Easter. We’re not changing churches or religions at this stage of the game. But when you say swastikas have nothing to do with us, that’s just not true.”

“Does Dad know?”

She smiles. “Of course he does. He’s very supportive. That’s why he’s been so upset over these swastikas. I know you think he only cares about Dino-land, but it’s mostly because of me. And you.”

It’s like the house is spinning all around me. How is it possible to wake up one person and, by the end of the day, you’re somebody else? Jewish? Not that there’s anything wrong with it, but it’s a thing I’m just not. I don’t even know anybody Jewish.

Well, not technically true. I know Dana—barely. She’s not from Chokecherry, but besides that, she’s pretty normal. And her dad can take a joke about dino poop, even when the joke is on him.

Finding out you’re different from what you thought you were is weird. But when the difference is basically nothing, how different are you? Not at all. Right?

Right?

“When were you planning on telling me this?” I ask. “Never?”

“You’re upset.”

“Of course I’m upset!” I explode. “All these years I’ve been somebody I didn’t even know I was! You’re supposed to tell me big things like this!”

She looks unhappy. “I’m sorry. I was waiting for the right time, and I guess it never came. Remember, I went through this myself three years ago, so I know how confused you must feel. But I eventually understood that I’m the same me. It’s an important thing to know about our past. But our present is what really matters. Our lives, our family—you, me, and Dad. That hasn’t changed at all.”

I back away. “You still should have told me.” Mom’s tearing up again, and I’m not in the mood to feel bad about it. For the past three weeks, we’ve done nothing but learn about intolerance and racism and Nazism and the Holocaust, and she never said one little peep about this. I think I have the right to be mad.

Dad too—he hasn’t shut up about the swastikas for five seconds since all this started. Didn’t it occur to him to mention that our family might have a special interest in it? That’s kind of a key piece of information, if you ask me. But nobody asks me anything.

So what now? According to Mom, I should just ignore the whole thing. But how’s that supposed to work? I picture the conversation with Jordie:

Me: What were you up to today?

Jordie: Played a little ball. Helped out my old man in the shop. You?

Me: Nothing much. I found out I’ve been the wrong religion my whole life. Wanna play some Xbox?

Or a text exchange with Pouncey:

Pouncey: How ru?

Me: Jewish

I’m not really serious, but it suddenly hits me—Pouncey’s grandfather was in the KKK. And Pouncey’s dad is a notorious jerk about practically everything … and that includes being racist. I’ve never heard Mr. Pouncey say anything against Jewish people, but that’s only because he doesn’t know any Jewish people.

Correction: He doesn’t think he does. I’m Jewish. Part Jewish. Twenty-five percent.

True, that doesn’t mean anything about Pouncey himself. But it’s kind of uncomfortable.

It wasn’t uncomfortable yesterday, even though I understood how awful the Klan was. What’s different? Yesterday I didn’t know.

So much for Mom’s idea that nothing has changed. Another lie.

To be fair, my parents didn’t technically lie. But only because it never occurred to me to ask them, “Say, we wouldn’t happen to be Jewish, would we?”

Mom thinks this is no biggie. She got used to it; why can’t I? It’ll fade into the background as soon as my life gets busy again, with friends, sports, school—

At the thought of the school, I get a clear vision of the big red swastika, freshly painted in the atrium. It’s the same symbol, same color, same right angles. But I can feel the hair on the back of my neck standing up at the sight of it. I picture Grandma, as a little baby, being handed over to total strangers. And never seeing her family again.

My mind runs through everything we learned about Nazi Germany these past three weeks of tolerance education, and during the Holocaust unit in fifth grade. It used to seem like ancient history … but this happened to my family. Where are my cousins on Grandma’s side? They were never born, because their parents and grandparents were murdered by the Nazis.

I feel like I’m losing it. All these ideas are whirling around my brain, building up the pressure until my skull starts to crumble. I’ve got to find a way to let it out—talk to somebody maybe. But who?

My parents?

They’re the ones who kept me in the dark all these years.

My friends?

They’d be just as weirded out as I am.

Is there anyone around here who’d understand?

I have swastika anxiety.

I see them everywhere—in clouds, in wallpaper patterns, in the weave of a rug. Once your brain goes in that direction, it’ll drive you crazy. I see one in my spaghetti, and no matter how many times I push my dinner around with a fork, the noodles keep re-forming into that awful pattern.

Eventually, my little brother, Ryan, notices me staring into the bowl with a murderous look in my eyes. So he takes that as the okay to reenact the Battle of Gettysburg on his plate, complete with sound effects of gunfire and muted cries of “Charge!” Pretty soon, tomato sauce is splattering all over the table.

Dad sighs. “If you don’t like it, you two, you don’t have to eat it. But please stop making a mess.”

This from a guy who spends his days carving fossils out of sandstone using a chisel and a paintbrush. He usually comes home looking like he’s taken a mud bath—at least that’s what my mother says. She works with the scientists too, cataloging their finds. So she stays clean most of the time.

The only thing worse than seeing swastikas where they’re not is dreading where they’ll turn up next. Whoever’s doing all this must feel pretty strongly about it, because they’re putting the awful things everywhere—scratched into lockers, duct-taped to windows, decorating bulletin boards and display cases.

There have been a total of eight incidents, and nobody has a clue who’s doing it. The school has even hired extra security to try to catch the culprit in the act. So far no luck. They have only one theory—that the guilty party is a kid. Every day, six hundred of us show up for school, and there aren’t enough employees in the district and cops in town to spy on each and every one of us.

I don’t have to see it to know that a new swastika has popped up somewhere. Suddenly, people are being friendly to me and noticing I’m alive. How am I doing, they ask. How am I holding up, considering, you know. I get that they’re just trying to be nice. Does it make me a bad person that I find their sympathy almost as upsetting as the swastikas that bring it on? Andrew and the other Asian kids don’t get that kind of attention. And nobody worries about the Black and Latino kids, who probably don’t feel great about this either. It’s just me, the Jewish girl.

I can’t get past the feeling that this is just some juvenile delinquent trying to freak everybody out. And the worst part is, it’s working. All those stories from the seventies—burning crosses, Ku Klux Klan. What if our family becomes a target?

My parents have been checking in with me every day. I’m under strict orders to tell them if anyone says or does something threatening. They’re a little more hands off with Ryan—nobody wants to traumatize a second grader. But even he gets a nightly stealth interrogation: Have you noticed friends treating you differently lately? Have you been overhearing new words you don’t understand?

One day, he asks, “

What’s a swampika?”

Mom doesn’t miss a beat, almost like she was expecting it. “It’s a wet, muddy place where tadpoles and lizards live.”

She says it so naturally, so matter-of-factly, that my brother accepts it and moves on. I envy my little brother. I hope he gets to stay clueless forever, but I doubt it. The swastikas are big news and getting bigger.

Dad has been driving Ryan and me to school instead of making us walk. So much for “Kids don’t get enough fresh air and exercise anymore.”

I watch as Ryan slams the car door and scampers into his elementary school. “I wish I was seven. Ryan’s biggest worry is what flavor of pudding pop Mom packed in his lunch.”

Dad doesn’t take the bait, probably because he knows where I’m going with this. Sometimes, it’s not that great being raised by two PhDs. They’re always miles ahead of you. He steers our SUV into the road and starts across the neighborhood toward the middle school.

This time I say it outright. “Dad, do you think the university would transfer you and Mom to another town?”

He glances sideways at me. “Well, we were trying for Paris, but turns out there aren’t any Diplodocus skeletons buried under the Eiffel Tower.”

“It isn’t exactly fun, you know,” I complain, “being the only Jewish kid while all this swastika stuff is going on.”

He pulls up in front of the student drop-off. “Mom and I know it can’t be pleasant. We both grew up in places where we were far from the only Jewish kids … and we knew coming here would be an adjustment, even before these incidents began.”

“Yeah, but now—”

“From what I’ve seen, your school is staying on top of it. Nobody’s trying to sweep this under the rug. I believe they’ll find out who’s doing it. And my hope is that we’ll all see that it’s just thoughtless mischief and poses no danger to this family. However”—he looks me straight in the eye—“if you or your brother are unsafe in any way, we will not stay here. Period.”

“But I still have to go to school,” I conclude wearily.

“But you still have to go to school.”

Beware the Fisj

Beware the Fisj Slacker

Slacker The Medusa Plot

The Medusa Plot This Can't Be Happening at MacDonald Hall!

This Can't Be Happening at MacDonald Hall! The War With Mr. Wizzle

The War With Mr. Wizzle The Emperor's Code

The Emperor's Code Zoobreak

Zoobreak The Danger

The Danger Unsinkable

Unsinkable Jake, Reinvented

Jake, Reinvented No More Dead Dogs

No More Dead Dogs The Stowaway Solution

The Stowaway Solution The Juvie Three

The Juvie Three The Climb

The Climb Criminal Destiny

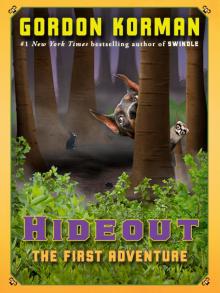

Criminal Destiny Hideout: The First Adventure

Hideout: The First Adventure Flashpoint

Flashpoint Swindle

Swindle Pop

Pop The Rescue

The Rescue Memory Maze

Memory Maze The Sixth Grade Nickname Game

The Sixth Grade Nickname Game Vespers Rising

Vespers Rising Collision Course

Collision Course The Abduction

The Abduction Losing Joe's Place

Losing Joe's Place The Dragonfly Effect

The Dragonfly Effect The Hypnotists

The Hypnotists Survival

Survival Lights, Camera, DISASTER!

Lights, Camera, DISASTER! Payback

Payback Ungifted

Ungifted Unplugged

Unplugged Framed

Framed Supergifted

Supergifted Masterminds

Masterminds Jackpot

Jackpot Don't Care High

Don't Care High The Deep

The Deep Go Jump in the Pool!

Go Jump in the Pool! The Contest

The Contest Public Enemies

Public Enemies Hideout: The Second Adventure

Hideout: The Second Adventure Chasing the Falconers

Chasing the Falconers One False Note

One False Note Shipwreck

Shipwreck Jingle

Jingle Unleashed

Unleashed Son of the Mob

Son of the Mob Now You See Them, Now You Don't

Now You See Them, Now You Don't War Stories

War Stories Schooled

Schooled Hunting the Hunter

Hunting the Hunter The Zucchini Warriors

The Zucchini Warriors A Semester in the Life of a Garbage Bag

A Semester in the Life of a Garbage Bag The Fugitive Factor

The Fugitive Factor Born to Rock

Born to Rock The Summit

The Summit Showoff

Showoff The Unteachables

The Unteachables The Third Adventure

The Third Adventure The Joke's on Us

The Joke's on Us Linked

Linked The Wizzle War

The Wizzle War The 6th Grade Nickname Game

The 6th Grade Nickname Game The Second Adventure

The Second Adventure The First Adventure

The First Adventure![39 Clues : Cahills vs. Vespers [01] The Medusa Plot Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/39_clues_cahills_vs_vespers_01_the_medusa_plot_preview.jpg) 39 Clues : Cahills vs. Vespers [01] The Medusa Plot

39 Clues : Cahills vs. Vespers [01] The Medusa Plot