- Home

- Gordon Korman

Linked Page 3

Linked Read online

Page 3

Wow. No wonder that swastika was such a big deal for the adults around here. It must have felt like the past was coming back to haunt them.

It’s crazy what a few lines of paint can do: I knew it would threaten the future for Dad, but I had no idea it would dredge up a long-forgotten past for the town.

Everybody thinks I might be the one who did the swastika just because I was the first person who saw it.

That’s how they talk about it too. It’s never who painted it or who drew it; it’s always who did it.

“Look at me.” I plead my case across the cafeteria table. “I’m Dominican. Why would I put a racist symbol on the school? People draw racist symbols to attack me!”

“Seriously?” Dana Levinson leans in from her spot three chairs down. “That happened?”

“I mean in theory,” I explain. “I’ve never experienced it in an in-your-face, swastika way. But for all we know, it was meant for me.”

“Or me,” adds Andrew Yee, who’s having lunch with Dana.

Caroline McNutt is mystified. “You guys aren’t Jewish.”

I roll my eyes. “They’ve been drilling it into our heads that a swastika isn’t just anti-Jewish, it’s anti-everybody—including a lot of white people who don’t live or think the same way as the white supremacists.”

“I just want this to be over,” Dana puts in wearily. “It started because we saw a swastika for about three minutes. And now what do we do all day every day? We look at swastikas.”

She has a point. Thanks to the tolerance education unit, we’ve seen pictures of swastikas on flags, on walls, on hats, on cars, on banners, on armbands, and on book covers. We’ve been shown film footage of Hitler’s Third Reich and rallies by vicious hate groups and white supremacists. We’ve pored over the images in our textbooks and in handouts. We’ve even photoshopped them into our Chromebooks, iPads, and PowerPoint presentations. I absentmindedly doodled one on my homework last night and had to tear it into a billion pieces and flush them down the toilet. That was fun—redoing my report at two in the morning just so nobody would think I’m the swastika guy. The theme may be “No Place for Hate,” but if there was anybody in our school who didn’t recognize the symbol on our atrium before, they sure as anything recognize it now.

“But you agree that it’s important, right?” I ask her. “We can’t just ignore what happened.”

She thinks it over. “I guess the only thing worse than doing all this would be doing nothing.”

“But it’s time to move on,” puts in Caroline, the seventh-grade president. “I mean, tolerance is important, but we’ve been doing it for almost two weeks. We’re way behind in planning the Halloween dance.”

I frown. “We have a Halloween dance?” I don’t remember one from last year.

“We should,” Caroline insists. “Normal schools do. Everybody always waits for the eighth-grade president to do everything. But our eighth graders are lazy. No offense.” She glances at eighth-grade Andrew.

“Hey, I’m from Massachusetts,” Andrew replies with a shrug. “This is only my school while the dig goes on. The minute my mom runs out of dinosaur bones to catalog, I’m history.”

“That’s a terrible attitude,” Caroline scolds. “By the time the dig’s over, you’ll be in high school. You’ll be stressing over SATs and ACTs and college admissions. Middle school should be the best years of our lives. And we’re wasting them obsessing over something almost all of us didn’t do that will probably never happen again.”

Caroline and I have sort of a history, me being president of the art club. Whenever Caroline has a brilliant idea, she always comes to me for posters to advertise it. Last December, my team and I did thirty-six posters advertising her school-wide Secret Santa—enough to put three in every hall in the building. We really knocked it out of the park. Thanks to the awesome job we did, every kid in Chokecherry knew about it. Guess who didn’t know about it—Principal Brademas. And when he put the kibosh on the whole thing, we were the ones who got yelled at, not Caroline. We were about three inches from having the whole art club shut down. I’m not sure what scares me more—the swastika in our atrium or the Halloween dance Caroline might make us all have.

As the tolerance education unit rolls into its third week, the only lesson anybody is learning is that you don’t have to be a racist to be sick of tolerance education. I think we minority students are more sick of it than anybody, since all the kids assume we want it, which we don’t. Each morning, when Mr. Brademas announces a new project we’re going to do, a new lecture we’re going to listen to, or a new film we’re going to screen, the groan coming from every classroom in the building is enough to rattle the windows. Nobody’s rude—there are no curses or catcalls or anything. We’re just done. Our tolerance for tolerance education has reached its limit.

Eventually, even the teachers get the message. I know something’s up when Brademas calls me to the office during my lunch period on Friday. He wants the art club to do a mural-size poster for the wall outside the office commemorating these past three weeks.

“Not the first part,” the principal says quickly. “You know, what started it all. Just a few of the highlights of the tolerance education unit.”

I can’t resist. “Does that mean the unit is over?”

“Yes,” he replies. “Please keep it to yourself. I’ll make the announcement at the assembly this afternoon.”

“Oh, sure,” I promise, and immediately go out and spread it all over the school. Being president of the art club doesn’t carry a lot of cred, so when I’ve got some inside scoop, I’m going to wake the town and tell the people. This could be the only chance I’ll ever get to approach kids who are too cool to talk to the president of the art club—even eighth graders and popular girls like Sophie Tavener and Pamela Bynes.

Naturally, I tell everyone to keep a lid on it. And just as naturally, they find the nearest person and blab. I’ll bet it doesn’t take forty-five minutes before the big news reaches every ear. There’s an air of electricity as we all file into the gym to hear what we already know.

It’s probably a good thing that I spilled the beans beforehand, because we’re pretty quiet and respectful when the principal makes the announcement. If it hadn’t been for me and my big mouth, we might all have jumped up and cheered. That could have convinced Brademas that we need more tolerance education.

“I want to thank each and every one of you for the maturity and dedication that you’ve shown over the past three weeks,” the principal concludes. “It was an unpleasant thing that brought us to this place, but I believe we’re better people for it. We may never know who drew that ugly symbol, and what their purpose might have been: a sick joke, vandalism against the school, or something more sinister. But whatever the reason, it’s in the past, and we can all be happy about that.”

Something more sinister. I let the words sink in. They seem to say that, as one of only a handful of minority kids, maybe I should have been more freaked out than I actually was.

“And now,” Mr. Brademas continues, “on to happier matters. It’s time to congratulate our baseball team on their championship season this past spring.”

That’s the reason this assembly is taking place in the gym instead of the auditorium. It’s time to unfurl the banner honoring the Chokecherry Cheetahs. It’s kind of a sore point with me. Brademas uses the art club as unpaid labor for every poster and sign that goes up in the school. But when one of his precious sports teams accomplishes something, he has the banner made professionally, rolled up, and revealed in dramatic fashion in front of six hundred cheering kids.

I console myself with the thought that it’s probably not going to happen again for a while. Our star athlete, Link Rowley, has been yanked out of sports because his father got steamed up over some prank gone wrong. I can’t even remember which one—with Link and his pals, it’s always something. So we’re probably going to stay banner-free through soccer season and potentially basketball too.

/>

The percussionist from the orchestra launches into a drumroll. At the top of a tall ladder, Mr. Kennedy loosens the twine, and the banner unfurls down the wall. The band launches into the first few notes of our fight song and falls silent. That matches the strangled gasps from the six hundred students.

The banner reads: SOUTHWESTERN COLORADO MIDDLE SCHOOL BASEBALL LEAGUE CHAMPIONS. But that’s not what anybody sees. Covering the length and breadth of the fabric is a stark swastika painted in splotchy black gunk.

This time, there’s none of the excitement that greeted the first swastika in the atrium. No phones appear to capture the moment in pictures and selfies. We’ve all been through three weeks of tolerance education, so we know exactly what we’re looking at.

Something to be afraid of.

My dad’s company, Duros Construction, does roofing and roof repair all around Chokecherry and Shadbush County.

Thanks a lot, Dad.

The thing is, Swastika 2.0—the one on the baseball banner—is painted in roofing tar. So the cops come to our house and search the adjoining office and warehouse. Guess what they find—roofing tar. Gallons of the stuff.

Dad’s a smart aleck about it. “What do you want me to put on a roof? Bubble gum? Cole slaw?”

Cops have no sense of humor about that kind of joke. “Your boy’s a seventh grader, isn’t he?” Sheriff Ocasek muses with a squint eye in my direction.

Dad sticks up for me. “What’s that supposed to mean?”

The sheriff shrugs. “Access to the tar. Access to the school. You do the math.”

Anyway, they leave eventually. But I don’t like the way they’re looking at me. A lot of people in town are looking at me the same way. Or maybe I’m just being paranoid. Having your place searched by police does that to a guy.

It doesn’t help that our local paper, the Shadbush County Daily, does a whole spread on the swastika thing.

SECOND RACIST SYMBOL RAISES MEMORIES OF TOWN’S DARK PAST

School officials in Chokecherry were dismayed to find a second swastika painted on middle school property, this one on a banner celebrating the baseball team. This proves that the first incident three weeks ago was far from a random occurrence. The Shadbush County Sheriff’s office is investigating, but still has no clear picture as to who might be behind the racist, anti-Semitic acts.

Much of the ethnic diversity in Chokecherry comes from visiting paleontologists involved in the dinosaur excavation sponsored by Wexford-Smythe University. However, there is no evidence as yet to suggest that the scientists and their families are the targets of the vandalism, although several of their children do attend the middle school.

“We’re not there yet, but we’ll find this guy,” Sheriff Bennett Ocasek promised at a news conference at Chokecherry city hall. “Nobody should be allowed to get away with this kind of thing.”

“Nothing like this has ever happened in our town before,” added George Rowley, owner of Chokecherry Real Estate and president of the local chamber of commerce.

That statement is not strictly accurate. As recently as the 1970s, Shadbush County was home to an active chapter of the Ku Klux Klan. Longtime residents have not forgotten 1978’s infamous Night of a Thousand Flames, when KKK groups from all over the West gathered in the county and ringed the foothills around Chokecherry with burning crosses …

Luckily, the article doesn’t say anything about roofing tar or Duros Construction. But it gives me a bad feeling.

“You should read this,” I tell Link. “They quote your dad.”

The three of us are walking to school on Monday morning. That’s where the paper comes from. We pass this news box every day, and Pouncey knows just where to kick it for the lid to open and give us a freebie. We usually look for our names on the local school sport report, but this swastika business is getting bigger than everything right now.

“Read it?” Link echoes bitterly. “My dad screamed the house down over it this weekend. He’s afraid that any bad press for the town is going to ruin his chances of getting that dino park he’s got his heart set on and turning Chokecherry into the next Orlando.”

“Maybe it’s payback,” I suggest. “He took away your soccer season, and the price turns out to be one dino park.” My thoughts turn more serious. My eyes drift across the foothills that circle the town, and I try to picture being surrounded by burning crosses in the darkness. “That Night of a Thousand Flames thing. Doesn’t sound like the Chokecherry I know.”

“My father says it’s ‘hogwash,’ ” Link puts in. “Is that even a word?”

“I know, right?” I high-five him. “Chokecherry’s too boring for a big thing—even a bad big thing.”

“Fake news,” Link adds. “The Daily is so thrilled to finally have something to write about that they’re losing their minds.”

“My dad was there,” Pouncey says from out of nowhere, gazing off into the distance.

“Your dad was where?” I ask him.

“The Night of a Thousand Flames,” he replies in a quiet voice.

“In 1978?” Link demands.

“He was five,” Pouncey explains. “My grandfather brought him. You know how my dad’s a jerk? Well, his dad was an even bigger one. He was in the Klan. He was in worse things than that. I guess a ring of burning crosses was his version of taking your kid out fishing.”

Link holds his head. “Do me a favor: Never tell that story at my house. I’ve never seen my old man so uptight. And you know the worst part? My mom’s worse. She freaked when she heard about the second swastika, and she doesn’t give a hoot about Dino-land. She’s the one who begged my dad not to invest all our savings buying up property where he thinks the resorts and golf courses are going to be.”

I remember when Pouncey’s grandfather died a few years ago. Not a lot of people went to the funeral. Maybe that’s why—everybody remembered the KKK connection. I was clueless—I was just a little kid, there to support my friend. But it’s creepy to think back, now that I know what the old man was involved in.

“But your dad’s not in the Klan, right?” I ask.

Pouncey shrugs. “I don’t lose too much sleep thinking about my family. Bad enough I have to live with them. But I don’t think the Klan operates around here anymore. All that was back in the seventies and before.”

As we step onto school property, Link brings up something I hadn’t considered. “You know the worst part of this? I bet tolerance education isn’t over anymore. It’s going to be like Groundhog Day, where every morning it starts over again.”

“I can’t stop thinking about those six million paper clips at that school in Tennessee,” I say. “I had a dream that was us and somebody drove up with one of those giant crane magnets from the car wrecking yards.”

Pouncey snorts. “Maybe collecting thirty million paper clips was the only way for those guys to get their teachers to stop tolerance education.”

The bell is only ten minutes away, so the lawn is crowded with kids. I wonder if any of them heard about the roofing tar, so they think I might be Swastika Guy. I see a lot of eyes on us, but that’s normal. All the girls look at Link, since he’s kind of the star athlete in town, and I’m not too shabby myself. But then I spot Dana Levinson’s gaze on me, and there’s nothing admiring about it. It’s no coincidence that the girl with the most reason to be anti-swastika is staring at someone who’s a prime suspect for being Swastika Guy.

“What did I do?” I blurt in her face, and she rushes away.

At the corner of the building, four Twister mats have been pegged into the grass, and about a dozen kids are wrapped around each other, pretzel-style. Caroline McNutt holds the spinner and seems to be running the game.

“Left foot—green!”

There’s some shifting around, a lot of giggles, and some screams as two players bump heads. A sixth grader tumbles to the mat and has to join the spectators on the grass.

“What’s going on?” Link asks.

“Get in the game

!” Caroline invites. “Link’s joining!” she exclaims far too loudly.

Link hangs back. “No, I’m not.”

“What gives, Caroline?” I ask. “Why is it so important to give people a chance to throw up their breakfast?”

She goes on the defensive. “Normal schools do fun things. We’ve been such a bunch of sad sacks lately. It’s my job as seventh-grade president to brighten things up a little.”

“Considering what’s been happening around here,” Link points out, “maybe people aren’t in a Twister mood.”

“That’s the whole point,” she explains. “If we give in and get depressed, then the swastikas win. This is how we fight back.”

“With Twister?” I ask.

“By living our lives!” she rants. “By showing whoever’s doing this that a few ugly symbols aren’t going to change the people we are!”

“It’ll take more than swastikas to make me play Twister,” Pouncey puts in.

“Oh, come on!” Caroline grabs him by the sleeve and tries to haul him onto the game, but she doesn’t make much progress. Stronger people than Caroline have tried to move Pouncey. He’s weighted on the bottom, like a punching clown.

The roar of a big engine captures everyone’s attention. Around the corner of the building, a big delivery truck starts up and pulls away from the school’s receiving dock. As it turns onto the driveway, we can now see the dumpster that stands next to the loading bay. It’s there, painted in dazzling white on the dark metal bin.

Swastika number three.

Beware the Fisj

Beware the Fisj Slacker

Slacker The Medusa Plot

The Medusa Plot This Can't Be Happening at MacDonald Hall!

This Can't Be Happening at MacDonald Hall! The War With Mr. Wizzle

The War With Mr. Wizzle The Emperor's Code

The Emperor's Code Zoobreak

Zoobreak The Danger

The Danger Unsinkable

Unsinkable Jake, Reinvented

Jake, Reinvented No More Dead Dogs

No More Dead Dogs The Stowaway Solution

The Stowaway Solution The Juvie Three

The Juvie Three The Climb

The Climb Criminal Destiny

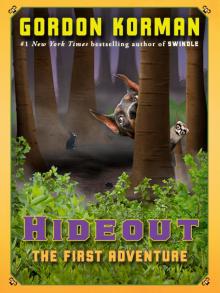

Criminal Destiny Hideout: The First Adventure

Hideout: The First Adventure Flashpoint

Flashpoint Swindle

Swindle Pop

Pop The Rescue

The Rescue Memory Maze

Memory Maze The Sixth Grade Nickname Game

The Sixth Grade Nickname Game Vespers Rising

Vespers Rising Collision Course

Collision Course The Abduction

The Abduction Losing Joe's Place

Losing Joe's Place The Dragonfly Effect

The Dragonfly Effect The Hypnotists

The Hypnotists Survival

Survival Lights, Camera, DISASTER!

Lights, Camera, DISASTER! Payback

Payback Ungifted

Ungifted Unplugged

Unplugged Framed

Framed Supergifted

Supergifted Masterminds

Masterminds Jackpot

Jackpot Don't Care High

Don't Care High The Deep

The Deep Go Jump in the Pool!

Go Jump in the Pool! The Contest

The Contest Public Enemies

Public Enemies Hideout: The Second Adventure

Hideout: The Second Adventure Chasing the Falconers

Chasing the Falconers One False Note

One False Note Shipwreck

Shipwreck Jingle

Jingle Unleashed

Unleashed Son of the Mob

Son of the Mob Now You See Them, Now You Don't

Now You See Them, Now You Don't War Stories

War Stories Schooled

Schooled Hunting the Hunter

Hunting the Hunter The Zucchini Warriors

The Zucchini Warriors A Semester in the Life of a Garbage Bag

A Semester in the Life of a Garbage Bag The Fugitive Factor

The Fugitive Factor Born to Rock

Born to Rock The Summit

The Summit Showoff

Showoff The Unteachables

The Unteachables The Third Adventure

The Third Adventure The Joke's on Us

The Joke's on Us Linked

Linked The Wizzle War

The Wizzle War The 6th Grade Nickname Game

The 6th Grade Nickname Game The Second Adventure

The Second Adventure The First Adventure

The First Adventure![39 Clues : Cahills vs. Vespers [01] The Medusa Plot Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/39_clues_cahills_vs_vespers_01_the_medusa_plot_preview.jpg) 39 Clues : Cahills vs. Vespers [01] The Medusa Plot

39 Clues : Cahills vs. Vespers [01] The Medusa Plot