- Home

- Gordon Korman

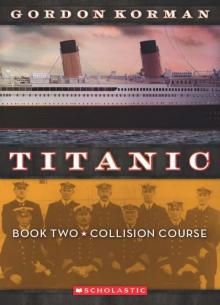

Collision Course Page 6

Collision Course Read online

Page 6

He dashed around the corner, leaped the gate, and slipped into the side entrance of the Verandah Café.

It was one of the most stunning rooms on the ship, featuring ivy-covered black lattice on the walls and immaculate white wicker furniture. The café was deserted except for a lone server collecting dirty dishes. He stared at the newcomer in dirty coveralls. “You can’t be in here!”

“They sent me to help clean up,” Paddy panted.

“What? Dressed like that?”

Paddy heard footsteps outside the door and knew he had no time to argue with the waiter. “I’m supposed to help!” He grabbed the tray from the bewildered man, tipped it up, and flipped the contents toward the door.

His timing could not have been more perfect. As Lightoller entered, he was pelted with drinks, cold coffee, and half-finished desserts. Glassware and ashtrays shattered at his feet.

Paddy bolted out of the café, leaving a trail of overturned tables in his wake. It wouldn’t slow down the second officer much, but he hoped it would give him enough of a cushion to disappear.

He sprinted along the passageway, looking left and right for a ladder or stair — anything that would get him off A Deck. There it was — a steep stewards’ ramp. He ran for it, disappearing just as Lightoller burst from the café.

Seeing no sign of his quarry, the second officer reached for the communication telephone on the bulkhead.

Paddy’s ramp bypassed B Deck and went directly to C. As he ran down the passageway, he kicked out of his coveralls and left them on the carpet behind him. Let them think he was on C. Let them search every compartment and storeroom. That ought to keep them busy for a while. He would be nowhere near here.

He took the stairs to E Deck and wheeled onto Scotland Road. Following this route, he could be all the way forward in the bow of the ship in minutes, far from Lightoller’s last sighting of him.

He slowed down to a brisk walk. Scotland Road wasn’t as busy now as it was during the day. But there were certainly crew about, and too much obvious haste would attract their attention. He received a few curious glances, and wondered whether scuttling the coveralls might have been a mistake. He was in the shirt and breeches of a third-class boy again, and that wasn’t the best costume for the working parts of the ship.

But he never made it to the bow, or anywhere near it. After perhaps fifty yards, he spied a sailor talking on one of the bulkhead telephones. More important, that sailor spied him.

If the thought had occurred to him a few seconds later, he probably would have been caught.

He’s speaking to the bridge! They’ve got a ship-wide alert for me!

He fled, leaping the rail of an access ladder and climbing down out of view. As he descended, the very ship around him seemed to fade out. He was suspended in darkness, clinging to the rungs in what seemed to be an endless vertical passage.

Noises swelled — a mechanical thrum punctuated by a vibration he could feel in his gut. Now he knew what lay below him. He had found the way down to the ship’s vast reciprocating engines.

As his eyes adjusted to the low light, he could make out a system of heavy piping, which brought in the steam that turned huge armatures. They looked otherworldly and alive, like the arms of giants performing a never-ending ritual.

At last he saw the deck, and stepped off onto something solid. With a sinking heart, Paddy spotted the engineer and recognized the device at his ear — a telephone receiver. Even here, in the bowels of the ship, Lightoller had found him.

In growing panic, Paddy understood that the game had changed. He was quick enough and smart enough to avoid a single officer aboard this floating city. But thanks to the Titanic’s communication phones, he was now the prey of more than nine hundred crew members, not just one.

With his heart thumping in his chest, he ran straight into the heart of all that massive machinery, hoping to disappear amid the forest of supports that held the engine in place. Over his shoulder, he caught sight of a mammoth armature plunging toward him.

In a blind panic, he flung himself to the deck. He closed his eyes, waiting to be squashed like a bug by tons of steel.

CHAPTER TWELVE

RMS TITANIC

SATURDAY, APRIL 13, 1912, 10:35 P.M.

The huge mechanical appendage swung down through the bottom of its range of motion, passing inches above Paddy’s cowering form.

“Come on out, lad,” the engineer called. “You can’t hide forever.”

Paddy raised his head slightly, casting his eyes over his surroundings. Had he well and truly trapped himself here? The Titanic was so vast and interconnected that there was almost always another path….

He spotted it between two support pillars — a small hatch in the forward bulkhead. Even if it led straight out the side of the hull into the ocean, he had already decided to go there. He peered up at the armatures, timing their motion. The instant the head space was clear, he was sprinting for the opening.

“Stop!” the engineer cried.

But before the man could translate his words into action, Paddy was through the hatch. The blast of heat nearly knocked him backward.

The furnaces! I’m in Number 1 Boiler Room!

Spitting ash, he scampered past a coal bunker, risking a glance to the rear. The engineer stumbled after him, bellowing at top volume. Paddy could distinctly make out the word “stowaway.”

Now the fat’s in the fire.

He fairly flung himself at the access ladder, scrambling like a monkey. Within seconds, he could feel the vibration of pursuers below him. A reaching hand grabbed his boot, and he kicked frantically, making contact with something solid. A muffled cry of pain, and he was free again. He scrambled up on deck and looked around wildly. He was on F now — just aft of the third-class dining saloon.

Running along the passage, he glanced over his shoulder and counted four crewmen chasing him — the angry engineer followed by three stokers. The scene reminded Paddy of a child’s storybook Daniel had shown him about an English fox hunt. At the time, Paddy had felt sorry for the fox.

Now I am the fox!

He dashed into the darkened third-class galley, searching for a place to hide. There were nooks and crannies aplenty, but nowhere that he wouldn’t be discovered by someone who was looking hard enough.

The indecision cost him precious seconds. The door swung open, slapping against the bulkhead. Bright light from the corridor penetrated the kitchen. There was no time to flee. In another instant, the crewmen would be upon him.

Acting on pure mindless instinct, Paddy rammed his shoulder into a stack of crates. Falling boxes hit the deck, sending the engineer sprawling. The wooden sides splintered apart, and, all at once, eleven large cantaloupes were rolling across the deck like a wave. A stoker’s boot came down on a spinning melon. With a cry of dismay, the man went down, bowling out the two pursuers behind him.

Paddy pounded through the third-class dining saloon, vaulting over long communal tables and benches. Back in the passageways, he felt the difference right down to the tips of his toes — the soft, thick carpeting of a first-class corridor. Some of the Titanic’s most luxurious features were on this part of F Deck — the heated saltwater swimming pool and the legendary Turkish steam bath.

Neither held the slightest interest for Paddy now. Escape was his singular thought.

He knew where he was heading without consciously deciding to go there — as if his legs were under the control of a puppeteer. It was the one hiding place aboard ship he’d hoped he’d never have to use — a place so cold, so dark, so dreadful that it made the hair stand up on the back of his neck just to think about it. Only if there was no other choice, he’d told himself when he’d first discovered it.

At a full gallop, he reentered the working part of the ship, jogging left and right as he made his way toward the prow. He could feel the bulkheads closing in as the hull tapered. He raced through the firemen’s quarters, past sleeping stokers, trying his best to skim silently ac

ross the deck.

When he saw the hatch, he pulled up short, almost choking on the lump that suddenly rose in his throat.

The pounding feet in the distance made the decision for him. It was either the misery that lay beyond this hatch, or the brig with the murderous Gilhooleys. No contest.

He threw open the heavy door to be greeted by a blast of frigid air and the overpowering smell of lubricant. And there it was, the Titanic’s anchor chain, a vast pile of enormous black links, each of them nearly Paddy’s full height.

He stepped out onto the curved, stout iron, finding it slick with grease. This was even more dangerous than he’d originally feared. He looked down. There was nothing to see but chain, folded in upon itself, all the way to the bilge of the ship, some forty feet below. Above him, the chain disappeared into the narrow shaft that stretched all the way to where the anchor hung on the starboard side of the prow.

He straddled the link and wrapped his arm around another. Only then did he feel secure enough to reach out and pull the hatch shut behind him. The darkness was almost smothering, enveloping him like a black velvet curtain. He unhitched his suspenders and tied them around the heavy iron, hoping against hope that they would support his weight in case he slipped. He seriously doubted that they would. If he dozed and lost his purchase on the link, he would be bruised, bloody, and dashed to pieces in the bilge. By the time his body was discovered there, if indeed it ever was, he would be nothing but a pitiful pile of broken bones.

Time passed with such agonizing slowness that minutes seemed like months. Paddy had no way of clocking his ordeal, yet he knew one thing for certain: He had to stay in the chain locker as long as was humanly possible. Second Officer Lightoller was not the sort of man who gave up easily. This search was going to take all night.

He shuddered, which made the grease run up his arms and down his legs. Paddy Burns had survived much in his fourteen years.

He was not at all certain he was going to survive this.

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

RMS TITANIC

SUNDAY, APRIL 14, 1912, 6:10 A.M.

It wasn’t sleep, exactly, but rather a frozen stupor brought on by exhaustion, bone-chilling cold, and the cramping of every muscle in his body in the effort to maintain his perch on the greasy anchor chain. The terror of falling had now become so old that he was losing his sharpness — even dozing a little. And disaster could be the only result of that.

How long had he been in this otherworldly place? It was impossible to tell. Long enough to lose feeling in his arms and legs. If he ever got out of here — if he ever opened that hatch and returned to the land of the living, he was by no means sure that his body would support him.

The hatch!

It was then that he realized that he was looking at the hatch. Its edges were lined with faint light. That meant daylight, morning.

I’ve survived the night!

For all the horror he’d already endured, this next move was surely the riskiest. He was about to open the hatch and quite possibly step into the arms of some stoker, who would deliver him directly to Mr. Lightoller’s swift justice.

But it had to be done. Five more minutes here and he might never recover enough to save himself. He undid the suspenders that were holding him in place. They fell and he never heard them land. Then he reached over, unlocked the hatch, and swung the door wide. An instant later, with more pain than he’d ever dreamed imaginable, he was standing on the deck, trembling and faint with fatigue.

But he was alone! By sheer luck, he had managed to find a moment in which all the firemen were gone from their quarters — a shift change, perhaps.

He took a step toward the door and froze. Slimy lubricating grease dripped from him with every movement. A quick self-inspection revealed that he was covered with the stuff from head to foot.

The urge to run — to get out of here before the stokers returned — was almost overwhelming. He fought it down. Begrimed with sludge, he’d leave a trail of black wherever he went.

He stripped off his filthy clothes and stepped into the adjoining shower room. The water was nearly scalding, yet the heat brought life to his numb fingers and toes, and eased the stiffness in his muscles. It was lucky that firemen used strong, gritty soap to combat the boilers’ ash, because the muck on his skin did not remove easily. After much scrubbing, he turned off the spray, feeling strangely awake and alive. For Paddy, a wash usually meant a swim in an ice-cold lake or river. Hot water and real soap was quite a luxury.

He pulled on a pair of coveralls hanging on a hook, rolling up the cuffs several times at the wrists and ankles. Kicking on his boots, he strode out of the shower room — and very nearly collided with the stoker standing by one of the bunks.

Paddy cast his gaze down to the deck. “Morning,” he mumbled in the deepest voice he could muster.

“How do you know my son?” the man demanded. “How do you know Alfie?”

Oh, Lord, Alfie’s father!

Paddy toyed with trusting in his natural gift of blarney and trying to talk his way out of this. But more crewmen could be coming any minute — and surely some of them knew about last night’s manhunt. Perhaps Mr. Huggins himself did. There was suspicion in his gruff voice….

With a cry of “I’m late!” Paddy dove for an access ladder and began a hurried descent, made agonizing by the aching of his arms and legs. He had no idea where he was going — possibly down to the hostile territory of the boiler rooms.

No. Cargo surrounded him, lashed to angled bulkheads. He was in the forward hold, just aft of the bow’s peak.

That means it isn’t far to the baggage room!

He dashed through the fireman’s passage and burst through the familiar hatch.

His exhaustion mingled with a surge of triumph. He’d been on the run for eight hours, but he’d made it.

He slipped under the netting and crawled into the large steamer trunk that was the closest thing to a safe place he would ever know aboard the Titanic. Curled up on Mrs. Astor’s fine linens, he fell into the deepest sleep he could remember.

When Alfie was shaken awake in his bunk, he very nearly swallowed his heart.

Lightoller! He saw me last night!

But as he blinked the sleep out of his eyes, he was relieved to find his father bending over him.

“Da?” John Huggins almost never left the stokers’ realm in the nether regions of the Titanic. Since sailing day, Alfie had seen his father only once or twice outside the orange-black glow of Number 5 Boiler Room.

The ash-stained face looked haunted. “Alfie, how do you know that boy?”

“Boy? What boy?”

“He brought water to the black gang yesterday,” his father prodded. “He spoke to me — mentioned you by name. He was in the firemen’s quarters just now, but he’s not one of us. What’s he to you?”

Alfie chose to play innocent, but his heart was sinking. He’d always feared that his association with Paddy would come to light. “I don’t know who you mean,” he lied. “There are many young crew members. Sometimes even the steerage boys help out for a few coins.”

John Huggins looked worried. “I hope to God you’re telling the truth, lad. There’s talk of a stowaway. And if you’ve aided him, it’s both our jobs. Where would we ever find work again with a blot like that on our records?”

With a growing sense of dread, the young steward realized that his father was right. Alfie’s own rash behavior and Paddy’s carelessness threatened to bring down all of them. New York was still some three days away. How would he ever keep this awful secret until then?

He felt the bulkheads of the crew quarters closing in on him.

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

RMS TITANIC

SUNDAY, APRIL 14, 1912, 7:45 A.M.

Rodney, Earl of Glamford, was never pleasant in the morning. This was usually thanks to his gaming losses and the crashing headache he suffered due to overindulging the night before.

Yet this morning, Juliana entered th

e parlor of their suite to find her father in a towering rage.

“I require an explanation of your behavior, miss!” he demanded harshly.

“I have no idea what you mean, Papa.”

“Do you not?” he raged. “Before you craft a proper lie, you should know that I witnessed your disgusting display — down in steerage, no less!”

Juliana worked hard to keep her expression neutral. Papa must not be allowed to see her humiliation at being exposed indulging in a pastime unbecoming the daughter of an earl. Amid the chaos of last night and her worry over what might have happened to Paddy, the one thing she thought she’d known for certain was that her father would be deep in a card game, oblivious to it all.

Alas, not so.

The old Juliana would have held her peace and taken the tongue-lashing meekly. But she was not the same girl that she had been at the start of this voyage. Her friendship with Sophie — and with Alfie and Paddy, too — had opened her eyes. Instead of blindly following a code of conduct that was centuries old, why not accept people of all stations with an open heart, and take kindness where you find it? In spite of the upsets of last night, she still remembered the glow of being welcomed into the third-class celebration.

“How peculiar,” she ventured demurely, “that in spite of your concern at my behavior, you were not waiting here in the cabin when I returned.”

“How dare you?” he retorted. “So distressed was I at the sight of you flouncing around like a common scullery maid that I required some companionship to settle my nerves!”

“Fifty-two companions, no doubt. That is, I believe, the number of cards in a deck.”

Enraged, he raised a hand to her, but thought better of it when she stood her ground and did not flinch. When he spoke again, his voice was softer, but no less angry. “Stupid girl, there are factors at play here that you cannot possibly begin to grasp.”

For some reason, she thought of Sophie’s mother — Amelia Bronson’s outrage at being denied the vote. Until this moment, Juliana had not seen what was so important about casting a ballot for a prime minister you would probably never meet. Now she understood perfectly. What galled Mrs. Bronson — what should gall all women — was the belief that no female was intelligent enough to make her own decisions.

Beware the Fisj

Beware the Fisj Slacker

Slacker The Medusa Plot

The Medusa Plot This Can't Be Happening at MacDonald Hall!

This Can't Be Happening at MacDonald Hall! The War With Mr. Wizzle

The War With Mr. Wizzle The Emperor's Code

The Emperor's Code Zoobreak

Zoobreak The Danger

The Danger Unsinkable

Unsinkable Jake, Reinvented

Jake, Reinvented No More Dead Dogs

No More Dead Dogs The Stowaway Solution

The Stowaway Solution The Juvie Three

The Juvie Three The Climb

The Climb Criminal Destiny

Criminal Destiny Hideout: The First Adventure

Hideout: The First Adventure Flashpoint

Flashpoint Swindle

Swindle Pop

Pop The Rescue

The Rescue Memory Maze

Memory Maze The Sixth Grade Nickname Game

The Sixth Grade Nickname Game Vespers Rising

Vespers Rising Collision Course

Collision Course The Abduction

The Abduction Losing Joe's Place

Losing Joe's Place The Dragonfly Effect

The Dragonfly Effect The Hypnotists

The Hypnotists Survival

Survival Lights, Camera, DISASTER!

Lights, Camera, DISASTER! Payback

Payback Ungifted

Ungifted Unplugged

Unplugged Framed

Framed Supergifted

Supergifted Masterminds

Masterminds Jackpot

Jackpot Don't Care High

Don't Care High The Deep

The Deep Go Jump in the Pool!

Go Jump in the Pool! The Contest

The Contest Public Enemies

Public Enemies Hideout: The Second Adventure

Hideout: The Second Adventure Chasing the Falconers

Chasing the Falconers One False Note

One False Note Shipwreck

Shipwreck Jingle

Jingle Unleashed

Unleashed Son of the Mob

Son of the Mob Now You See Them, Now You Don't

Now You See Them, Now You Don't War Stories

War Stories Schooled

Schooled Hunting the Hunter

Hunting the Hunter The Zucchini Warriors

The Zucchini Warriors A Semester in the Life of a Garbage Bag

A Semester in the Life of a Garbage Bag The Fugitive Factor

The Fugitive Factor Born to Rock

Born to Rock The Summit

The Summit Showoff

Showoff The Unteachables

The Unteachables The Third Adventure

The Third Adventure The Joke's on Us

The Joke's on Us Linked

Linked The Wizzle War

The Wizzle War The 6th Grade Nickname Game

The 6th Grade Nickname Game The Second Adventure

The Second Adventure The First Adventure

The First Adventure![39 Clues : Cahills vs. Vespers [01] The Medusa Plot Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/39_clues_cahills_vs_vespers_01_the_medusa_plot_preview.jpg) 39 Clues : Cahills vs. Vespers [01] The Medusa Plot

39 Clues : Cahills vs. Vespers [01] The Medusa Plot