- Home

Page 2

Page 2

Beware the Fisj

Beware the Fisj Slacker

Slacker The Medusa Plot

The Medusa Plot This Can't Be Happening at MacDonald Hall!

This Can't Be Happening at MacDonald Hall! The War With Mr. Wizzle

The War With Mr. Wizzle The Emperor's Code

The Emperor's Code Zoobreak

Zoobreak The Danger

The Danger Unsinkable

Unsinkable Jake, Reinvented

Jake, Reinvented No More Dead Dogs

No More Dead Dogs The Stowaway Solution

The Stowaway Solution The Juvie Three

The Juvie Three The Climb

The Climb Criminal Destiny

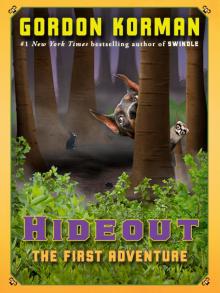

Criminal Destiny Hideout: The First Adventure

Hideout: The First Adventure Flashpoint

Flashpoint Swindle

Swindle Pop

Pop The Rescue

The Rescue Memory Maze

Memory Maze The Sixth Grade Nickname Game

The Sixth Grade Nickname Game Vespers Rising

Vespers Rising Collision Course

Collision Course The Abduction

The Abduction Losing Joe's Place

Losing Joe's Place The Dragonfly Effect

The Dragonfly Effect The Hypnotists

The Hypnotists Survival

Survival Lights, Camera, DISASTER!

Lights, Camera, DISASTER! Payback

Payback Ungifted

Ungifted Unplugged

Unplugged Framed

Framed Supergifted

Supergifted Masterminds

Masterminds Jackpot

Jackpot Don't Care High

Don't Care High The Deep

The Deep Go Jump in the Pool!

Go Jump in the Pool! The Contest

The Contest Public Enemies

Public Enemies Hideout: The Second Adventure

Hideout: The Second Adventure Chasing the Falconers

Chasing the Falconers One False Note

One False Note Shipwreck

Shipwreck Jingle

Jingle Unleashed

Unleashed Son of the Mob

Son of the Mob Now You See Them, Now You Don't

Now You See Them, Now You Don't War Stories

War Stories Schooled

Schooled Hunting the Hunter

Hunting the Hunter The Zucchini Warriors

The Zucchini Warriors A Semester in the Life of a Garbage Bag

A Semester in the Life of a Garbage Bag The Fugitive Factor

The Fugitive Factor Born to Rock

Born to Rock The Summit

The Summit Showoff

Showoff The Unteachables

The Unteachables The Third Adventure

The Third Adventure The Joke's on Us

The Joke's on Us Linked

Linked The Wizzle War

The Wizzle War The 6th Grade Nickname Game

The 6th Grade Nickname Game The Second Adventure

The Second Adventure The First Adventure

The First Adventure![39 Clues : Cahills vs. Vespers [01] The Medusa Plot Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/39_clues_cahills_vs_vespers_01_the_medusa_plot_preview.jpg) 39 Clues : Cahills vs. Vespers [01] The Medusa Plot

39 Clues : Cahills vs. Vespers [01] The Medusa Plot