- Home

- Gordon Korman

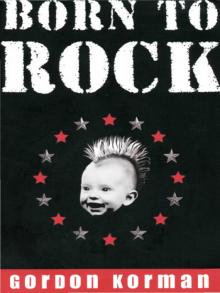

Born to Rock Page 12

Born to Rock Read online

Page 12

“Llama!” Even yelling for a dog, King had an iconic punk voice, a piercing rasp full of what Melinda called the Three A’s: Anger, Angst, and Anarchy.

“Llama!” My own effort was anemic by comparison.

“Come on, Leo, a real scream comes from your spleen. Listen—” He stuck his head and shoulders out the car window and unleashed a “Llama!!!” that lifted downtown Denver off its bedrock foundation.

A chorus of “Hey, pipe down!” and “Shut up, man!” rang out in the neighborhood around us.

He shrugged. “Critics. Okay, you try.”

“I don’t even know where my spleen is,” I protested.

“It isn’t rocket science, Leo. Just think about something that pisses you off and let fly.”

That was easy. I conjured up a mental picture of graduation day—smug Borman at the dais, bragging about me getting into Harvard, knowing full well that my scholarship was history. I felt my spleen then, a deep wellspring of suppressed fury, a reservoir of pure McMurphy. The rage began to bubble over, the pressure building. It wasn’t a question of yelling; I just had to loosen the valve:

“LLAMA!!!” It echoed off warehouses and offices.

He looked impressed. “We’ll make a punk rocker out of you yet.”

“Is that all there is to it?”

“You know what punk is? A bunch of no-talent guys who really, really want to be in a band. Nobody reads music, nobody plays the mandolin, and you’re too dumb to write songs about mythology or Middle-earth. So what’s your style? Three chords, cranked out fast and loud and distorted because your instruments are crap and you can’t play them worth a damn. And you scream your lungs out to cover up the fact that you can’t sing. It should suck, but here’s the thing—it doesn’t. Rock and roll can be so full of itself, but not this. It’s simple and angry and raw.”

I was wide-eyed. “That’s how Purge started?” It didn’t sound much like the version of events in Melinda’s project.

“That’s how everybody started,” King assured me. “The Ramones, the Sex Pistols, X. Sure, we all got better musically. That comes with practice. But what makes it punk—that has to be there on day one.”

I could picture King young and hungry like that. But Max, Zach, and Neb seemed like neurotic middle-aged guys, obsessed with personal issues, weight issues, and health issues. Not exactly what you’d expect of the Angriest Band in America.

“Back in the eighties,” I ventured, “was the whole band, you know, like you?”

He didn’t pretend to misunderstand. “You mean crazy? It’s easy to be crazy when you’re broke and starving. But it’s hard to keep it up in a Benz. It’s all about authenticity. The one thing you don’t want to be in this business is a poser.”

I remembered Dad using that word in the suite at the St. Moritz. Dad and bio-dad on the same page—the mind boggles. “Are you posing when you’re onstage now?”

He thought it over. “It’s just harder to care so much. In the old days, Reagan would do something, and I’d get so steamed I’d be ready to jump into the audience and start ripping off heads. Today, if the government does something I don’t like, I know the sun’s still going to rise tomorrow. It’s fifty times tougher to get my energy level where it needs to be for a performance. I can still do it, but it wipes me out.”

I gave him a crooked smile. “So the old King Maggot’s gone forever?”

He looked tired. “Maybe I didn’t get fat, bald, divorced, and herniated. But I’m just as middle-aged as the others. Still—” He flipped up his shades, and his dark eyes were gleaming. “I like to think that if something came along that was really worth caring about, I could get just as worked up as I used to in the eighties.”

“That’s why people with plate glass windows are nervous.”

He groaned. “I barely remember that day. Everybody else does, though. The damn Harley has become an extension of my butt. That’s rock and roll for you. Ozzy bit the head off a bat, and I rode a Harley through a window. And nobody’s going to let either one of us forget it.”

It’s funny, I’d always thought of Purge’s antics as vandalism, drug-induced insanity, and publicity stunts. Never in a million years would it have occurred to me that it had anything to do with caring. Not that I wanted to ride a chopper through a window, but suddenly my own life seemed very blah. I couldn’t imagine feeling that strongly about something.

“It must have been amazing,” I said wistfully.

“The hospital said I broke the record for stitches.”

“Not the injuries; the caring. You know, caring that much.”

“I wasn’t exactly Gandhi. Most of the time I just busted stuff up. I was usually high.” He looked embarrassed. “That’s not what you say when you’re learning to be a father, is it?”

I pulled up short. Learning to be a father? Since when?

“Don’t worry,” I soothed. “I had plenty of chances to be a burnout before this summer. In high school, the drugs are there if you go looking for them. I was into other things.”

“Like the Young Republicans?”

I stared at him. “How do you know about that?”

“I Googled you. That’s my drug of choice these days. Bernie’s got Viagra; I’ve got a laptop.”

I pictured myself on Graffiti-Wall.usa, spying on Melinda’s blog, while King was at his own computer in another part of the hotel. Father and son Web-surfing, another family trait like the earlobe. I was amazed. Not that he found me online—I knew that my name appeared on the Young Republicans’ Web site. I just couldn’t picture this punk icon keyboarding the words “Leo Caraway” in the search field.

“Did it say they kicked me out?”

“No kidding. Did they have a pretzel machine, too?”

I was treading perilously close to my real reason for being on Concussed. I gave him the expurgated version. “They said I helped this kid cheat on a test.”

“Did you?”

“Depends on how you look at it. But the problem wasn’t what happened. It was that I refused to help the assistant principal get the other guy kicked out of school.”

His eyebrow shot up. “See, that doesn’t sound very Republican.”

“There’s nothing wrong with hard work and personal responsibility,” I said righteously. It was the beginning of a lecture I’d given to a lot of unbelievers, cribbed from a stump speech by Congressman DeLuca himself. But extolling The Common Sense Revolution to King Maggot? He was the opposite of common sense. He had built a legendary career on a foundation of chaos, gut impulse, and rage.

An awkward silence followed. It underscored the chasm that separated my bio-dad and me. A fruitless poodle search couldn’t span that gap. Neither could the Golden Gate Bridge. I was still a Republican, and he was still a McMurphy.

We were literally saved by the dogcatcher. A panel truck came around the corner and parked in front of an all-night diner. The driver got out and went inside.

I stared at the lettering on the door. It read: CITY OF DENVER ANIMAL CONTROL.

Something in the back barked.

And then the Republican and McMurphy were grinning at each other.

“If that’s Llama,” King vowed, “I’m going to church.”

I had to admit it was a pretty sweet piece of timing.

We got out of the van and approached the truck from behind. I joined my bio-dad at the small window in the rear door. Mesh pens lined both sides of the payload, five across and stacked three high. Only three of the thirty enclosures were occupied. There was a yappy mongrel, a strange-looking animal that appeared to be some kind of muskrat, and—fast asleep in the far cage, bottom level—

A large white poodle.

“Jackpot,” said the front man of Purge.

The door was unlocked. We entered to a barrage of outraged barking from the mongrel.

“Hey, Llama,” King greeted the poodle. “How’s it going, boy?”

Llama opened a baleful eye and glared at us.

> “Penelope trained him well,” remarked my bio-dad. “He’s got her personality, not just her good looks.”

I decided to take the initiative. This was my errand of mercy. And as a Purge staffer, I couldn’t let King get his microphone hand bitten off.

I flipped open the latch, grabbed Llama by the collar, and hustled him out of the truck, and over to the van. King threw open the cargo doors, and we pushed Llama inside. He promptly curled into a ball and went back to sleep.

Our smooth operation was interrupted by a booming voice: “Hey—you can’t take that animal!”

Enter one very angry dogcatcher, his breakfast rudely interrupted.

We scrambled into the van and I gunned the motor. Much of the tread of our tires was transferred to the pavement as the rental screeched away.

I flew through central Denver, wheeling left and right down anonymous streets, in a desperate bid to disappear fast. I sneaked a sideways look at King, who was practically cackling with exhilaration.

“What?” I demanded.

“My son, the Young Republican.” He didn’t seem entirely repulsed by the idea.

“Ex–Young Republican.” And if Fleming Norwood knew about this, he’d probably blackball me again.

“You can slow down, Leo,” King added. “They don’t do high-speed chases in animal control.”

It was getting light by the time we hauled Llama into the plush lobby of our hotel. After the late night at the Pretzel, I figured everyone would still be asleep. But Max sat at a table in the restaurant, feeding slabs of Belgian waffle to a large white poodle.

“Morning,” he called, sounding tired, but otherwise none the worse for wear. “Whose dog is that?”

What were the odds? Another poodle in the right place at the right time.

We had kidnapped the wrong dog.

“Yours,” King told him.

“Nobody’s like my Llama,” the drummer enthused. “Can you believe he found his way back here? Just showed up at valet parking ten minutes ago.”

“Congratulations,” said his lead singer. “Now you’ve got a pair.”

“You thought that was Llama?” Max was amazed. “Can’t you see that’s a bitch?”

King stifled a yawn. “Definitely.” And he started for the elevator.

I was chagrined. “I’m so sorry, King. I never should have dragged you out of bed over this. I totally overstepped.”

My bio-dad looked surprised. “Are you kidding? That’s the best time I’ve had in years. But wake me before noon and you’re a dead man.”

The mirrored doors swallowed him up, leaving me standing there, hyperventilating.

Well, he didn’t hate me. That was something.

Now what was I going to do with this dog?

DENVER, CO (AMALGAMATED WIRE SERVICE):

City of Denver Animal Control denied earlier reports that a purebred poodle was stolen from one of its mobile units by two unidentified white male suspects while the officer had breakfast in a downtown luncheonette.

“We prefer to focus on positive developments,” said a department spokesman, citing an upcoming series of public service announcements featuring Purge lead singer King Maggot.

[19]

THE STRESS OF HIS DIVORCE WAS turning Max into an oddball. He refused to get on the plane from Denver to Kansas City, opting instead for an eleven-hour drive with Cam in the equipment truck that held his beloved drum kit.

Not that I was complaining. I got to fly on Max’s first-class ticket. This burned Cam up no end. “What about unloading the stuff?”

“I’ll meet you guys at the fairgrounds in KC,” I promised.

It came straight from King, so there was no point in arguing. By then, everybody on the tour knew about my special status as Prince Maggot, which set me apart from the other roadies. It was seriously interfering with Cam’s plan to treat me like snail slime. I almost felt bad for the guy. Anybody who spent so much time talking about hooking up with women, but so little of actually doing it had to be in a permanent foul mood.

Cam wasn’t the only one getting snippy as Concussed continued east. Bernie was annoyed at having to smooth over the dognapping affair, and fly King back to Denver to record public service announcements. Zach was bristling because a smart-alecky reviewer had referred to him as Zach Fatzenburger. Now Bernie was threatening to hire a professional dietician “…for the health of the band.”

Speaking of the health of the band, Purge had heard from Neb Nezzer, who was out of the hospital and recovering with his family. He said he’d be ready to rejoin Concussed for the European leg of the tour. That was the topic of discussion on the flight—how to tell Neb he was out of a job.

“Pete’s the future,” was Bernie’s opinion.

The squabbling was widespread. The other three Stem Cells were grumbling that Pete was more interested in his temporary gig with Purge than his permanent one with them. All four Dick Nixons were staying at separate hotels. Chemical Ali had fired two managers; one in Vegas, and one in Phoenix. Skatology’s lead singer stood accused of sending love notes to Mark Hatch’s wife.

King shrugged it off. “Touring is a pressure cooker.”

He was the one person who seemed immune to the infighting. Just as he’d traded all-night partying for the World Wide Web, he held himself aloof from the backbiting. Maybe it was because, as the true superstar of Concussed, he could afford to. But I was beginning to think it was because he really was aloof.

Onstage, he was as ferocious as ever. At the Kansas City show, the fury of his lyrics blew ripples in the jumping crowd like straight-line winds through a field of wheat. Knowing that it no longer came naturally, I couldn’t help but be impressed by the ultimate professional plying his trade.

It was the part of the set where King launched into his usual anachronistic harangue about President Reagan’s invasion of Grenada. I frowned. Something wasn’t right. Sure, he was all wound up and ranting. But this had nothing to do with the ’80s. What was he saying?

“…fifteen thousand shares of Apple Computer!…twenty-five thousand shares of Altria Group!…seventeen thousand five hundred shares of Citibank Financial!…”

The heat of the Missouri summer turned ice-cold. All at once, I realized where my bio-dad was getting this new material. I recognized it instantly. It was my mock stock portfolio from the Web site of the Young Republicans of East Brickfield Township High School.

“This is all we care about!” King howled. “Corporations…money…profit!”

How stupid I was to feel that we were finally connecting! To be flattered that he cared enough to look for me on the Web! And what had the search brought him? Not his long-lost son, but new material to update his attack on President Reagan. I was the new Grenada.

I listened, stunned, as tens of thousands of throats bellowed their repudiation of my prizewinning portfolio. It was a game—a mildly interesting time-waster for a bunch of high school kids who followed the stock market. Yet right then, if King had pointed me out, I swear the crowd would have fallen on me and torn me to pieces. Such was the power of my bio-dad to incite a mob the size of an army.

The ultimate professional plying his trade.

As it turned out, I was a professional too. The fact that I was an employee of Purge was the only thing that kept me from walking out of there.

As we climbed out of the Sunbelt to St. Louis and Chicago, the audiences grew tougher. The novelty of warm weather had worn off, and the crowds expected something huge to make fourteen sweaty, often rainy, hours worthwhile. The pressure inevitably fell on Concussed’s headliners. They delivered, but it was killing them. Maybe twenty-year-old Pete could coke himself up into the Energizer Bunny, but Zach and Max were ready to drop. And although he showed it less, I could tell the tour was taking a lot out of King, too.

Melinda exemplified the new audience tone—still worshipful, but God help the band that disappointed her.

KafkaDreams:

Mark Hatch has pierced his n

ose so many times that the cartilage is gone and he can’t sing anymore. During the primal scream solo in “Pus,” he had to stop for breath. What a poser! It isn’t primal if you have to take two shots at it….

I hadn’t seen her since that searing night when Owen and I had pulled her off one of Phoenix’s finest. My info came from Graffiti-Wall, and from Owen, who stopped by a few times to say hi, and to mooch free food from the backstage catering spread. He was probably on a mission from Melinda herself, since he always made a point of mentioning that she was still mad at me for preventing her from protecting King. She had no way of knowing that I’d already seen my semi-forgiveness online.

“The two of us probably saved her a night in jail,” I grumbled. “How come I’m in the doghouse, but nothing sticks to you? You were right there with me.”

He shrugged. “Aw, you know Mel.”

“No, I don’t,” I said honestly. “I’ve been hanging around the girl since the cradle, but I really don’t have the faintest idea what might be going on inside her head.”

“You’ve got to look at it from her perspective. King used to be hers. But how can being his fan compete with being his son?”

“That’s only because she sets it up that way,” I argued. “Me being his son doesn’t change the music.”

He shook his head. “You still don’t get it.”

As a peace offering, I wangled them backstage passes for the Milwaukee show. It was more a gesture of mercy than anything else. It had been pouring for a day and a half. The county park that was serving as the concert venue was a mud bog below a buzzing, churning cloud of insects. Pole-mounted bug-zappers ringed the stage on three sides. When the music wasn’t playing, the sickening sizzle of fricasseeing creepies was pretty much continuous. Their tiny carcasses rained down like chimney soot.

The bands were pulling out all the stops today, pounding through explosive sets with a mixture of sympathy and respect. Only die-hard fanatics would brave such conditions for a concert.

By now, Max had evolved the simple process of setting up his drum kit into an advanced science. We had to treat his precious skins like spun crystal so he could beat the crap out of them during the show. Cam and I were the only roadies he trusted. Personally, I could have lived without the honor.

Beware the Fisj

Beware the Fisj Slacker

Slacker The Medusa Plot

The Medusa Plot This Can't Be Happening at MacDonald Hall!

This Can't Be Happening at MacDonald Hall! The War With Mr. Wizzle

The War With Mr. Wizzle The Emperor's Code

The Emperor's Code Zoobreak

Zoobreak The Danger

The Danger Unsinkable

Unsinkable Jake, Reinvented

Jake, Reinvented No More Dead Dogs

No More Dead Dogs The Stowaway Solution

The Stowaway Solution The Juvie Three

The Juvie Three The Climb

The Climb Criminal Destiny

Criminal Destiny Hideout: The First Adventure

Hideout: The First Adventure Flashpoint

Flashpoint Swindle

Swindle Pop

Pop The Rescue

The Rescue Memory Maze

Memory Maze The Sixth Grade Nickname Game

The Sixth Grade Nickname Game Vespers Rising

Vespers Rising Collision Course

Collision Course The Abduction

The Abduction Losing Joe's Place

Losing Joe's Place The Dragonfly Effect

The Dragonfly Effect The Hypnotists

The Hypnotists Survival

Survival Lights, Camera, DISASTER!

Lights, Camera, DISASTER! Payback

Payback Ungifted

Ungifted Unplugged

Unplugged Framed

Framed Supergifted

Supergifted Masterminds

Masterminds Jackpot

Jackpot Don't Care High

Don't Care High The Deep

The Deep Go Jump in the Pool!

Go Jump in the Pool! The Contest

The Contest Public Enemies

Public Enemies Hideout: The Second Adventure

Hideout: The Second Adventure Chasing the Falconers

Chasing the Falconers One False Note

One False Note Shipwreck

Shipwreck Jingle

Jingle Unleashed

Unleashed Son of the Mob

Son of the Mob Now You See Them, Now You Don't

Now You See Them, Now You Don't War Stories

War Stories Schooled

Schooled Hunting the Hunter

Hunting the Hunter The Zucchini Warriors

The Zucchini Warriors A Semester in the Life of a Garbage Bag

A Semester in the Life of a Garbage Bag The Fugitive Factor

The Fugitive Factor Born to Rock

Born to Rock The Summit

The Summit Showoff

Showoff The Unteachables

The Unteachables The Third Adventure

The Third Adventure The Joke's on Us

The Joke's on Us Linked

Linked The Wizzle War

The Wizzle War The 6th Grade Nickname Game

The 6th Grade Nickname Game The Second Adventure

The Second Adventure The First Adventure

The First Adventure![39 Clues : Cahills vs. Vespers [01] The Medusa Plot Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i2/04/10/39_clues_cahills_vs_vespers_01_the_medusa_plot_preview.jpg) 39 Clues : Cahills vs. Vespers [01] The Medusa Plot

39 Clues : Cahills vs. Vespers [01] The Medusa Plot